Towards Kyoto

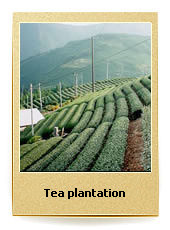

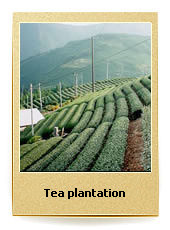

We bid farewell to our mountain – Fuji-san. As we failed to reach its top, we were troubled by a sense of insufficiency, but in fact we did all we could at that time – that was it! We still had a few days and 500 km of mountainous roads ahead of us before we reached Osaka, from where we were to set off for Poland. We decided to up the tempo, because we wanted to have at least one day for sightseeing in Kyoto – the most beautiful city of Japan. Before we reached it, we passed the region of Shizuoka, with its countless tea plantations. We even spent a night at one of them. Well, we could not find any better overnight accommodation. There wasn't even enough space for our tent, so having spotted a secluded tea plantation, we rolled out our sleeping bags between rows of neatly trimmed bushes. The ground, lined with rice bran, was very soft. It was also damp, especially in the morning. Both out sleeping bags and the bikes were wet with dew. Rice bran stuck to the sleeping bags, so we looked really silly. In the morning I had a chance to take a closer look at the plantation. Nicely trimmed, rows of parallel bushes ran down a steep hill. There was a very characteristic smell in the air. That's what I like!

Over the next two days we cycled through medium-height mountains. Up and down, on and on. We passed some truly charming places, as if straight from a travel agent's brochure. Villages situated in small valleys made an especially lasting impression on me. Tea plantations, autumn-coloured leaves, lonely palm trees, babbling brooks, and blissful silence uninterrupted by roaring car engines – it all created a unique atmosphere of those places. We spent a night at a place owned by very friendly people. Our host was a school headmaster, so he spoke fairly good English. In order to show us hospitality, they even cooked potatoes for breakfast, which is very rare in Japan. Once again we could charge our "mental batteries", and accumulate energy for the next few days. As soon as we left the mountains, cities began to appear – one by one – forming a never-ending jungle of buildings. First there was the city of Toyota, then Nagoya, where we saw an old harbour and the Atsuta shrine – one of Japan's oldest (dating back from the 4th century) and most prominent places of worship. It is also referred to as "kusanagi-no-tsurugi", or "house of the sacred sword" which constitutes a part of royal regalia. In a big park, where you have an impression that the trees lean over your head and whisper prayers, there is a building which looks different from what we got used to, in terms of Japanese architecture. It has a simple steep roof (without the characteristic curved roof corners) crowned with a row of parallel balks. This style is typical of the early centuries AD – primal, free from Chinese influence. Starting from the 6th century AD, the "invasion" of Chinese culture began. Initially the Japanese would borrow and copy almost everything from the Central Nation – later they modified those patterns. Phenomena that had long been changed in China, or lost altogether, still functioned in its primary (or only slightly altered) form in Japan. Take the tea ceremony as an example, brought from China by Buddhist Zen monks. Even something as Japanese as the katana sword originates from China!

Over the next two days we cycled through medium-height mountains. Up and down, on and on. We passed some truly charming places, as if straight from a travel agent's brochure. Villages situated in small valleys made an especially lasting impression on me. Tea plantations, autumn-coloured leaves, lonely palm trees, babbling brooks, and blissful silence uninterrupted by roaring car engines – it all created a unique atmosphere of those places. We spent a night at a place owned by very friendly people. Our host was a school headmaster, so he spoke fairly good English. In order to show us hospitality, they even cooked potatoes for breakfast, which is very rare in Japan. Once again we could charge our "mental batteries", and accumulate energy for the next few days. As soon as we left the mountains, cities began to appear – one by one – forming a never-ending jungle of buildings. First there was the city of Toyota, then Nagoya, where we saw an old harbour and the Atsuta shrine – one of Japan's oldest (dating back from the 4th century) and most prominent places of worship. It is also referred to as "kusanagi-no-tsurugi", or "house of the sacred sword" which constitutes a part of royal regalia. In a big park, where you have an impression that the trees lean over your head and whisper prayers, there is a building which looks different from what we got used to, in terms of Japanese architecture. It has a simple steep roof (without the characteristic curved roof corners) crowned with a row of parallel balks. This style is typical of the early centuries AD – primal, free from Chinese influence. Starting from the 6th century AD, the "invasion" of Chinese culture began. Initially the Japanese would borrow and copy almost everything from the Central Nation – later they modified those patterns. Phenomena that had long been changed in China, or lost altogether, still functioned in its primary (or only slightly altered) form in Japan. Take the tea ceremony as an example, brought from China by Buddhist Zen monks. Even something as Japanese as the katana sword originates from China!

We left Nagoya without any regrets. Just another big city on our way. In the meantime we stopped by two unusual Shinto shrines. The first one – Tagata – was devoted to male fertility. We were lucky enough to witness a moment when six men carried the largest 5-metre phallic statue out of the temple (probably to get it renovated). Phallic monuments in all sizes were spread all over the place, ranging from 1 cm to 3 m. The other shrine – Oagata – focused on the female womb, yet in a more delicate manner. It was a considerable attraction for us – Europeans. In the Far East there are many temples like those two, any nobody is shocked.

We left Nagoya without any regrets. Just another big city on our way. In the meantime we stopped by two unusual Shinto shrines. The first one – Tagata – was devoted to male fertility. We were lucky enough to witness a moment when six men carried the largest 5-metre phallic statue out of the temple (probably to get it renovated). Phallic monuments in all sizes were spread all over the place, ranging from 1 cm to 3 m. The other shrine – Oagata – focused on the female womb, yet in a more delicate manner. It was a considerable attraction for us – Europeans. In the Far East there are many temples like those two, any nobody is shocked.

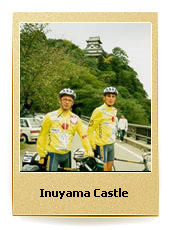

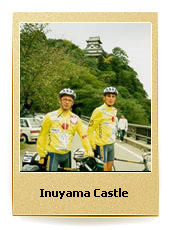

Afterwards we visited Inuyama, a city overlooked by a small caste. As we learned, it was the only such monument of Japanese architecture that had remained unchanged throughout history. Its former owner lived in it until 1972. Now it is open for visitors, but has remained a private property. This building is entirely different from European standards. Japanese castles were built upwards rather than laterally, as was the case in Europe. The goal was to obtain optimum visibility and to improve defensive qualities. This attitude prevailed until the times when artillery became more widespread. Coming back to the structure – the entire building frame is made of wood, even though it supports a tall four-storey building. It is a true masterpiece of the carpentry craft. Besides, there are still many carpentry masters in contemporary Japan. The storeys are connected by very steep stairs – one must be careful not to lose the head.

Afterwards we visited Inuyama, a city overlooked by a small caste. As we learned, it was the only such monument of Japanese architecture that had remained unchanged throughout history. Its former owner lived in it until 1972. Now it is open for visitors, but has remained a private property. This building is entirely different from European standards. Japanese castles were built upwards rather than laterally, as was the case in Europe. The goal was to obtain optimum visibility and to improve defensive qualities. This attitude prevailed until the times when artillery became more widespread. Coming back to the structure – the entire building frame is made of wood, even though it supports a tall four-storey building. It is a true masterpiece of the carpentry craft. Besides, there are still many carpentry masters in contemporary Japan. The storeys are connected by very steep stairs – one must be careful not to lose the head.

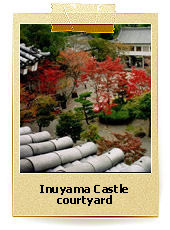

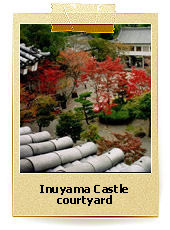

From the castle we went straight to Uraku-en park, one of the most beautiful tea parks in Japan. At least this was what we read in the guidebook. It was the first time we saw a genuine Japanese garden. At the entrance we were surprised that visitors were expected to take off shoes and put on special flip-flops. In my opinion it was exaggeration, but what could we do – no flip-flops, no sightseeing. The garden was magnificent indeed, perfectly groomed in every detail. Each shrub properly shaped, and each stone placed in the right spot. I dare say there are no better gardeners in the world than the Japanese.

From the castle we went straight to Uraku-en park, one of the most beautiful tea parks in Japan. At least this was what we read in the guidebook. It was the first time we saw a genuine Japanese garden. At the entrance we were surprised that visitors were expected to take off shoes and put on special flip-flops. In my opinion it was exaggeration, but what could we do – no flip-flops, no sightseeing. The garden was magnificent indeed, perfectly groomed in every detail. Each shrub properly shaped, and each stone placed in the right spot. I dare say there are no better gardeners in the world than the Japanese.

Unfortunately, from this oasis of peace and tranquillity we headed back towards the concrete jungle. Passing countless towns and cities, we reached Japan's largest freshwater lake – Biwako, situated just a stone's throw from Kyoto – the pearl among Japanese cities.

Over the next two days we cycled through medium-height mountains. Up and down, on and on. We passed some truly charming places, as if straight from a travel agent's brochure. Villages situated in small valleys made an especially lasting impression on me. Tea plantations, autumn-coloured leaves, lonely palm trees, babbling brooks, and blissful silence uninterrupted by roaring car engines – it all created a unique atmosphere of those places. We spent a night at a place owned by very friendly people. Our host was a school headmaster, so he spoke fairly good English. In order to show us hospitality, they even cooked potatoes for breakfast, which is very rare in Japan. Once again we could charge our "mental batteries", and accumulate energy for the next few days. As soon as we left the mountains, cities began to appear – one by one – forming a never-ending jungle of buildings. First there was the city of Toyota, then Nagoya, where we saw an old harbour and the Atsuta shrine – one of Japan's oldest (dating back from the 4th century) and most prominent places of worship. It is also referred to as "kusanagi-no-tsurugi", or "house of the sacred sword" which constitutes a part of royal regalia. In a big park, where you have an impression that the trees lean over your head and whisper prayers, there is a building which looks different from what we got used to, in terms of Japanese architecture. It has a simple steep roof (without the characteristic curved roof corners) crowned with a row of parallel balks. This style is typical of the early centuries AD – primal, free from Chinese influence. Starting from the 6th century AD, the "invasion" of Chinese culture began. Initially the Japanese would borrow and copy almost everything from the Central Nation – later they modified those patterns. Phenomena that had long been changed in China, or lost altogether, still functioned in its primary (or only slightly altered) form in Japan. Take the tea ceremony as an example, brought from China by Buddhist Zen monks. Even something as Japanese as the katana sword originates from China!

Over the next two days we cycled through medium-height mountains. Up and down, on and on. We passed some truly charming places, as if straight from a travel agent's brochure. Villages situated in small valleys made an especially lasting impression on me. Tea plantations, autumn-coloured leaves, lonely palm trees, babbling brooks, and blissful silence uninterrupted by roaring car engines – it all created a unique atmosphere of those places. We spent a night at a place owned by very friendly people. Our host was a school headmaster, so he spoke fairly good English. In order to show us hospitality, they even cooked potatoes for breakfast, which is very rare in Japan. Once again we could charge our "mental batteries", and accumulate energy for the next few days. As soon as we left the mountains, cities began to appear – one by one – forming a never-ending jungle of buildings. First there was the city of Toyota, then Nagoya, where we saw an old harbour and the Atsuta shrine – one of Japan's oldest (dating back from the 4th century) and most prominent places of worship. It is also referred to as "kusanagi-no-tsurugi", or "house of the sacred sword" which constitutes a part of royal regalia. In a big park, where you have an impression that the trees lean over your head and whisper prayers, there is a building which looks different from what we got used to, in terms of Japanese architecture. It has a simple steep roof (without the characteristic curved roof corners) crowned with a row of parallel balks. This style is typical of the early centuries AD – primal, free from Chinese influence. Starting from the 6th century AD, the "invasion" of Chinese culture began. Initially the Japanese would borrow and copy almost everything from the Central Nation – later they modified those patterns. Phenomena that had long been changed in China, or lost altogether, still functioned in its primary (or only slightly altered) form in Japan. Take the tea ceremony as an example, brought from China by Buddhist Zen monks. Even something as Japanese as the katana sword originates from China!

We left Nagoya without any regrets. Just another big city on our way. In the meantime we stopped by two unusual Shinto shrines. The first one – Tagata – was devoted to male fertility. We were lucky enough to witness a moment when six men carried the largest 5-metre phallic statue out of the temple (probably to get it renovated). Phallic monuments in all sizes were spread all over the place, ranging from 1 cm to 3 m. The other shrine – Oagata – focused on the female womb, yet in a more delicate manner. It was a considerable attraction for us – Europeans. In the Far East there are many temples like those two, any nobody is shocked.

We left Nagoya without any regrets. Just another big city on our way. In the meantime we stopped by two unusual Shinto shrines. The first one – Tagata – was devoted to male fertility. We were lucky enough to witness a moment when six men carried the largest 5-metre phallic statue out of the temple (probably to get it renovated). Phallic monuments in all sizes were spread all over the place, ranging from 1 cm to 3 m. The other shrine – Oagata – focused on the female womb, yet in a more delicate manner. It was a considerable attraction for us – Europeans. In the Far East there are many temples like those two, any nobody is shocked.

Afterwards we visited Inuyama, a city overlooked by a small caste. As we learned, it was the only such monument of Japanese architecture that had remained unchanged throughout history. Its former owner lived in it until 1972. Now it is open for visitors, but has remained a private property. This building is entirely different from European standards. Japanese castles were built upwards rather than laterally, as was the case in Europe. The goal was to obtain optimum visibility and to improve defensive qualities. This attitude prevailed until the times when artillery became more widespread. Coming back to the structure – the entire building frame is made of wood, even though it supports a tall four-storey building. It is a true masterpiece of the carpentry craft. Besides, there are still many carpentry masters in contemporary Japan. The storeys are connected by very steep stairs – one must be careful not to lose the head.

Afterwards we visited Inuyama, a city overlooked by a small caste. As we learned, it was the only such monument of Japanese architecture that had remained unchanged throughout history. Its former owner lived in it until 1972. Now it is open for visitors, but has remained a private property. This building is entirely different from European standards. Japanese castles were built upwards rather than laterally, as was the case in Europe. The goal was to obtain optimum visibility and to improve defensive qualities. This attitude prevailed until the times when artillery became more widespread. Coming back to the structure – the entire building frame is made of wood, even though it supports a tall four-storey building. It is a true masterpiece of the carpentry craft. Besides, there are still many carpentry masters in contemporary Japan. The storeys are connected by very steep stairs – one must be careful not to lose the head.

From the castle we went straight to Uraku-en park, one of the most beautiful tea parks in Japan. At least this was what we read in the guidebook. It was the first time we saw a genuine Japanese garden. At the entrance we were surprised that visitors were expected to take off shoes and put on special flip-flops. In my opinion it was exaggeration, but what could we do – no flip-flops, no sightseeing. The garden was magnificent indeed, perfectly groomed in every detail. Each shrub properly shaped, and each stone placed in the right spot. I dare say there are no better gardeners in the world than the Japanese.

From the castle we went straight to Uraku-en park, one of the most beautiful tea parks in Japan. At least this was what we read in the guidebook. It was the first time we saw a genuine Japanese garden. At the entrance we were surprised that visitors were expected to take off shoes and put on special flip-flops. In my opinion it was exaggeration, but what could we do – no flip-flops, no sightseeing. The garden was magnificent indeed, perfectly groomed in every detail. Each shrub properly shaped, and each stone placed in the right spot. I dare say there are no better gardeners in the world than the Japanese.

Unfortunately, from this oasis of peace and tranquillity we headed back towards the concrete jungle. Passing countless towns and cities, we reached Japan's largest freshwater lake – Biwako, situated just a stone's throw from Kyoto – the pearl among Japanese cities.