My impressions plus trivia

What is Madagascar like? It is difficult to answer this question in a few dozen sentences. However, although I only spent a month there and covered a distance of 2100 km, it was enough to observe some interesting phenomena. This journey gave me a chance to admire beautiful landscapes, and capture the beauty of Malagasy nature on photographic film.

Actually, the Malagasy are not black people, as you might think because of the geographical location of the island. They are the descendants of peoples originating from Indonesia, Asia Minor and Africa. Each of the 13 Malagasy tribes are characterised by distinct anthropogenic features. In the east of the island, local people have 'Polynesian' features, with occasional Mongoloid influences attributable to the sizeable population of Chinese origin. In the west, you can come across people with noticeably darker complexion and features typical of the black race. Moreover, there are many people of Pakistani and Indian descent. The latter comprise a hermetic caste, disallowing closer relations with the indigenous Malagasy.

The Malagasy are very friendly towards white foreigners, whom they call 'vazaha'. Sometimes I even didn't feel like greeting people back, when all village inhabitants – especially children – rushed to the street shouting 'Sali vazaha', which means 'Welcome, white foreigner'. I would hear 'Sali' dozens of times a day, and it was next to impossible to cycle through a village unnoticed. It may also happen that natives living in the bush are afraid of vazahas – rumour has it that white people devour hearts and brains of the Malagasy people. In general, however, vazahas are regarded as visitors from a dreamland where nobody needs to work much to have money – a lot of money. Since white people are so rich, why not make use of it? This is why you should haggle whenever you want to buy anything, thus standing a chance of reducing the price by half. Obviously, the prices are noticeably higher in areas frequented by foreigners.

Madagascar can surprise you with many interesting customs. Among typically local phenomena are 'fady' – taboos, or impure acts. For example, all Tuesdays and Thursdays are fady on almost the whole island. It is not suitable to work in the field on those days, as the crops may be poor, but it is a good time to trade or rest. The Malagasy are especially fond of the latter activity, since the climate undoubtedly fosters laziness. Bananas grow on trees, and a bowl of rice costs next to nothing. People say they do not even feel like wanting anything. Of course many natives are very busy people, but in most cases the Malagasy are not trying to compete with the Japanese. Coming back to fady Thursdays, it was not so long ago that in some regions children born on this day would be killed. Luckily, this barbaric ritual has been eradicated by missionaries. Unfortunately, they still have not coped with another practice, namely euthanasia. In some regions of Madagascar elderly or ailing people are 'put to sleep' with a pillow, and frequently a priest is asked to perform the last rites a day before. A majority of the Malagasy are Catholics, but pagan customs are sometimes still given priority. Other intriguing practices are connected with a remarkably deep worship of ancestors. At the funeral, the body wrapped in a shroud is placed in a grave. After some time, however, it is exhumed during a solemn ceremony, wrapped in a new shroud, and placed in a tomb that tends to be decorated with paintings depicting the life and belongings of the deceased. Thus you can learn that the person was a taxi driver, or owned six bulls. Tombs and cemeteries are located at a certain distance from villages, and are regarded as sacred places, where strangers are not welcome. Each tribe builds tombs in a different way. The Betsimisaraka bury their dead under canoes. The Bari living near Ranohira build a stone post partly buried under rocks.

Family ties are very strong in Madagascar. It often happens that a well-off family member is exploited to the extreme. For example, your family can 'pay you a visit' and stay at your place for a year or even longer, or they will leave their children with you, claiming that local schools are better. Then, after a month, they no longer care about the offspring. As a result, few Malagasy decide to open their own business, fearing that it would be ravaged by the family even before the opening. After all, you cannot say 'no' to your family… Deviating from this custom would in fact force a Malagasy to cut off all contacts with the next of kin, which would be very difficult and painful.

Malagasy families are very large, the ideal model being 12 children: 6 boys and 6 girls, at least in the northeastern region. I have heard about a family in which the first daughter was actually the twentieth child! Groups of children can be seen everywhere. There is a school in almost every big village, crowds of laughing kids heading towards it each morning. Most village schools have only one big classroom, and only parents of children living in wealthy villages and towns can afford to buy them notebooks and pencils.

There is something uniquely beautiful about Malagasy children. They are always smiling, even if dirty and snotty-nosed, or wearing rags that we would not even use for wiping the floor. Children take care about one another, older siblings bringing up toddlers. Mothers frequently provide for the whole family, while fathers may experience various ups and downs. They often carelessly leave their wives and children to live with another woman. Faithfulness is a rarity in Madagascar, and the Bari tribe even accepts polygamy. However, men belonging to this tribe are more interested in collecting more zebu (bulls) rather than more wives.

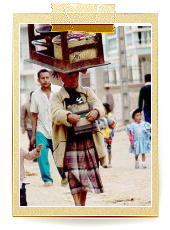

Women have the talent to carry practically anything on their heads. In the photo below you can see a Malagasy lady with a table on her head, plus a bucket and a basket on top of it all.

The Malagasy (especially men) do not pay much attention to clothing. One of characteristic garments is 'lamba' – a square of patterned cloth, which also helps carry a child on one's back. In villages pyjamas are treated as festive attire, excellent to wear in church. Shoes are a luxury that only the wealthy can afford – most people walk barefoot or in flip-flops.

Another interesting fact – all men's names begin with 'R', and 2 our of every 3 place names begin with the prefix 'Antana'.

Having elaborated on the curiosities of everyday life in Madagascar, I also think it is worth devoting some time to the fascinating local nature.

The route I covered on the Red Island (so named because of the omnipresent laterites – orange and brown tinted soils) encompassed several climate zones. The climate obviously has a clear impact on the surrounding landscapes. In the east I visited parts of the rainforest in d'Andasibe-Mantadia and Ranomafana National Parks. I was impressed by the dense thicket of plants I came across in the bush. As soon as you walk away from the track it is impossible to move forward without using a machete. Of course you do not need one in parks. A national park is the only place where you can spot lemurs and other interesting animals.

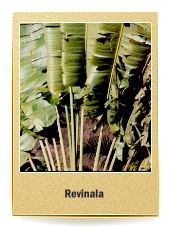

Forests have been destroyed in almost the whole territory of Madagascar, meaning that they are virtually non-existent. In more that 1500 years' history of the Malagasy civilisation, 3/4 of all forests have been cut down, and the process still continues. One of the reasons is that wood is a combustible material (used for charcoal production). Another reason is 'tavy' – a traditional farming method. People believe that such uncontrolled 'slash and burn' approach will ensure fertile fields. It is no use explaining that things are actually the other way round, erosion proceeding faster on exposed laterite soils. This process is further intensified by the sunlight and rainstorms, in comparison with which a typical Polish cloudburst is small beer. It is estimated that tavy may be blamed for as much as 30 percent of Madagascar's territory being set on fire each year! As a result, for example, the only thing left from Farafangana National Park is now an entrance sign. A few environmental organisations are running anti-tavy campaigns, attempting to manage national parks more effectively and prevent reckless practices. Such actions are of crucial importance, because the parks are the only shelter for endemic animals and plants, i.e. ones that cannot be found anywhere else in the world. A handful of facts should help you realise how unique Madagascar is. A territory twice the size of Poland is home to 3 percent of the world's flora species, 80 percent of which are endemic plants. Let us just mention tree ferns, reaching up to 10 m high, or 170 palm species (3 times more than can be found on the whole African continent). Please note that 97 percent of palm species are endemic. Among the most interesting plants is the Ravinala palm – one of the national symbols of Madagascar.

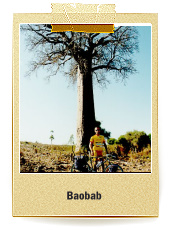

The leaves of this plant – otherwise referred to as Traveller's Palm – are aligned along the east-west axis, being a source of drinking water in emergency situations. However, I would recommend trying it only if you are extremely thirsty, because the sap has an unpleasant smell. In national parks you can admire beautiful orchids, as well as unusual Pachypodium succulents nicknamed 'Elephant's trunk' due to their looks – thin twigs with yellow flowers stemming from a thick and low bough. In the south of the island you can find baobabs – the trees that look as if they were growing upside down. The Red Island has 6 out of 7 baobab species in the world.

Those trees are unique – standing alone in savannah, as if forgotten. The Malagasy have found an unusual application for them. A few metres above the ground they cut a hole in the trunk, hollowing it out down to the ground level. The hollow space starts to collect water, which is pumped by the immense root system from the depths of the dry soil. Several Malagasy legends attempt to account for the looks of the tree. One of them says that when creating the Earth, God planted baobabs too. However, they grew too fast – against His will – stealing the sunlight from other plants. As a punishment, God pulled them out of the ground and planted them back, this time upside down. According to another legend, it was the Devil who planted the tree this way, because he wanted to have some greenery in hell.

As regards the fauna, a number of species once present in Madagascar are now completely extinct: the giant ground-dwelling Megaladapis lemur, a miniature hippopotamus, or Aepyornis – the largest bird to have ever walked on the surface of the Earth. It was over 3m tall and lay enormous eggs – 30cm high and 20cm in diameter.

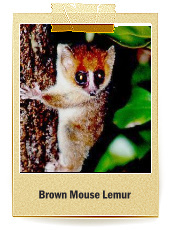

90 percent of animals living in Madagascar are endemic species, of which the most interesting are lemurs. I had an opportunity to take photos of many species of those animals, the nocturnal Brown Mouse Lemur (Microcebus Rufus) being the one I liked the most. It is just a little bigger that a mouse, but can jump between tree branches up to 2m away.

The island also prides itself on a rich variety of reptiles and amphibians: starting from 150 species of chameleons, through hundreds of frog species, to the Nile Crocodile. Bird watchers will be satisfied there as well, being able to spot birds of paradise, beautifully coloured kingfishers and bee-eaters.

We also need to mention the sea fauna and the coral reefs surrounding Madagascar, which are among the most impressive in the world. I even had a chance to glance at a tiny fragment of the reef when I dived in Ifaty. If it was so beautiful at the depth of just 3 m, I can imagine what is hidden deeper…

Finally, I would like to mention some facts related to the 'cycling part' of my journey. In my opinion, the greatest success was reaching the third highest peak of Madagascar – Tsiafajavona (2643 m). The climb was exhausting and difficult, with a 1000 m altitude difference at a distance of 30 km. The beautiful view from the mountaintop, followed by a crazy downhill ride, fully compensated for my effort. In the south of Madagascar there were some mountains, and savannah with hundreds of termite mounds. Cycling along a dirt road, I also crossed a desert with not even a single tree between myself and the horizon. Consequently, I could not find any shelter from the blazing sun that heated the air to 50 degrees Centigrade. All in all, I cycled for around 250 km on unpaved roads, which I will keep in my memory for a long time. The expedition lasted one month, giving me an opportunity to 'touch' Madagascar's attractions. In order to see some more interesting things, much more time is needed. I think one day I will return to Madagascar, but without a bike – this means of transport prevented me from exploring the most distant and wild corners of the Red Island.